In athletic endeavors, it is my observation that there are some who are very successful because they are talented and skilled in the activity they are performing. This can result from natural ability or dedicated, consistent, and well-designed practice or perhaps other reasons. There are other participants that are successful not because of their talent or skill, but because of their intensity. The person trying harder than their opponent has a distinct advantage. Going after a rebound in a basketball game like a starving man pursuing a morsel of food yields results far beyond the typical player who jumps up, halfheartedly hoping to come down with the ball. It is a rare and exceptional person who has both of these qualities: talent/skill and intensity. These are the people who become legends.

Thus, it is intensity that can turn a bad player into a good one, a good one into a a great, and a great into a legend. It is no different in designing software, marketing information products, or trying to take over the world.

Productivity

When addressing the goal of being more productive, the first place to start is in identifying the problems that keep us from having the productivity we desire. If you feel like you don’t get as much done as you should, or as much as you would like, or you just want to get more done or to finish what you are doing more quickly, you have to ask yourself why you aren’t already there. For most of us, the first and most obvious answer is distraction. That is certainly the case for me. When I am focused on the task at hand, things go much faster. When my mind is wandering, it’s a struggle. Sometimes I find myself sitting at my desk and trying to remember what it was I was trying to accomplish. This is not acceptable. You need to have focus to perform and to give your all. Focus is prerequisite for intensity. Intensity is the lynchpin to performance. Intensity coupled with skill creates Beast Mode.

So how do you address a lack of focus? What are the problems that prevent sustainable intensity? Typically, it is just that – sustainability. It is hard to stay focused throughout a day of trying to do serious work. We like to think of programmers, hopped up on caffeine, powering through problems with marathon coding sessions and all-night hack-a-thons. This is the image portrayed in movies and media. For a few folks, this might even work. It doesn’t work for me. Long and sustained intensity is just not in the cards. I know there are others like me and I’m certain it’s a majority. I’m confident it’s a vast majority and I have a suspicion it’s almost everyone. For those of us who aren’t super-human all night coders, an answer I have found to be effective toward the sustainability of focus and intensity is not to try to sustain it for too long.

When I play basketball, I know that I can only play at maximum intensity for a limited time before fatigue sets in and I have to either take a break from playing or reduce intensity. There are times that I may not consciously reduce my intensity, but it is effectively diminished as there is just less in the tank to fuel forward progress. This is more dramatic and pronounced in a physical activity like basketball and can be perceived by any casual observer. It is less externally obvious for a software developer or other desk-jockey, but it is not any less real. In fact, I’d argue it’s even greater when working with deep intensity in thought-primary activity like software, writing, or human interaction.

Thus, the answer, at least for me and for now, is less sustained time trying to be a badass programmer. Taking breaks from the activity of producing leads to greater productivity during the act when it is happening.

This is exactly the principle that drives the Pomodoro Technique, which I have found to be extremely useful and powerful.

A short description of the technique in my words is this:

- Work for short bursts of intense, flurry-style production, then take a short break.

- Cycle this with longer breaks every few cycles.

The canonical form of the technique is a cycle of working “Pomodoros”, meaning a 25-minute period of focused, intense, and productive labor. Following each Pomodoro, you take a break. The breaks are 5 minutes until you have completed 4 Pomodoros with 5 minutes between each, after which there is a 15-minute break. Then you can repeat this 4-Pomodoro cycle again following by another 15-minute break.

This canonical form with 25 minute sprints, 5 minute short breaks, and 15 minute long breaks was created by the originator of the technique, Francesco Cirillo. I have not ever found a justification for why 25 minutes is the Gospel on this. I suspect it’s pretty arbitrary and that 25-5 fits nicely into the clock and 2 Pomodoros, complete with breaks, take an hour. You, of course, are at liberty to play with the timings and find out if something else works for you. I have experimented with using both longer and shorter Pomodoros. At one point, I was convinced that for software development tasks, 50 minutes with 12 minute breaks in between was optimal for me and for writing and other types of activities, it was 15 or 20 and 5, like the standard, but just a bit shorter. I don’t do that anymore because the 50 minute timespan made it so much easier to get interrupted. It’s also more convenient to be able to have consistency across the different activities of the day and have “working for a Pomodoro” have the same meaning regardless of context. Because of these reasons, I have returned to the 25-5 formula and I think it works pretty well for me. While I still think programming is better served with longer intervals than other activities because of the dependency it has on context and deep concentration, 5 minutes is just enough to gain a fresh perspective on something without really breaking the context. Having longer breaks over this summer gave me opportunities to jump on the trampoline with my children and do other things more fun and invigorating that just urinating and filling my water cup and banging through my email.

One rule I think must be followed is that every break should involve movement. That can be as much or as little as is comfortable, but at minimum, you need to leave your chair. There has been much said recently about the toxicity of long periods of sitting and therefore the benefits of standings desks and the hyperbolic assertion that “sitting is the new smoking.” While there is certainly something to the idea that the amount of sitting done by office workers can be harmful, I’m not at all interested in giving up my chair. I’m satisfied with making sure I don’t stay glued to my seat all day for hours on end. Do what you will, but it is my position that having a practice of standing periodically throughout the day and walking around for a few minutes is adequate to make sure you’re not harming yourself excessively with sitting. Pomodoro is a natural and perfect fit for this policy.

Additional Benefits

Tracking time spent on tasks becomes easier with Pomodoros. Instead of trying to have a running clock and appending time to tasks haphazardly, you can start to look at Pomodoros as the unit of time you spent on something in measuring how long things took. You can also start to estimate tasks in terms of Pomodoros, which starts to have more meaning than using things like hours (tough I’m still a fan of story points).

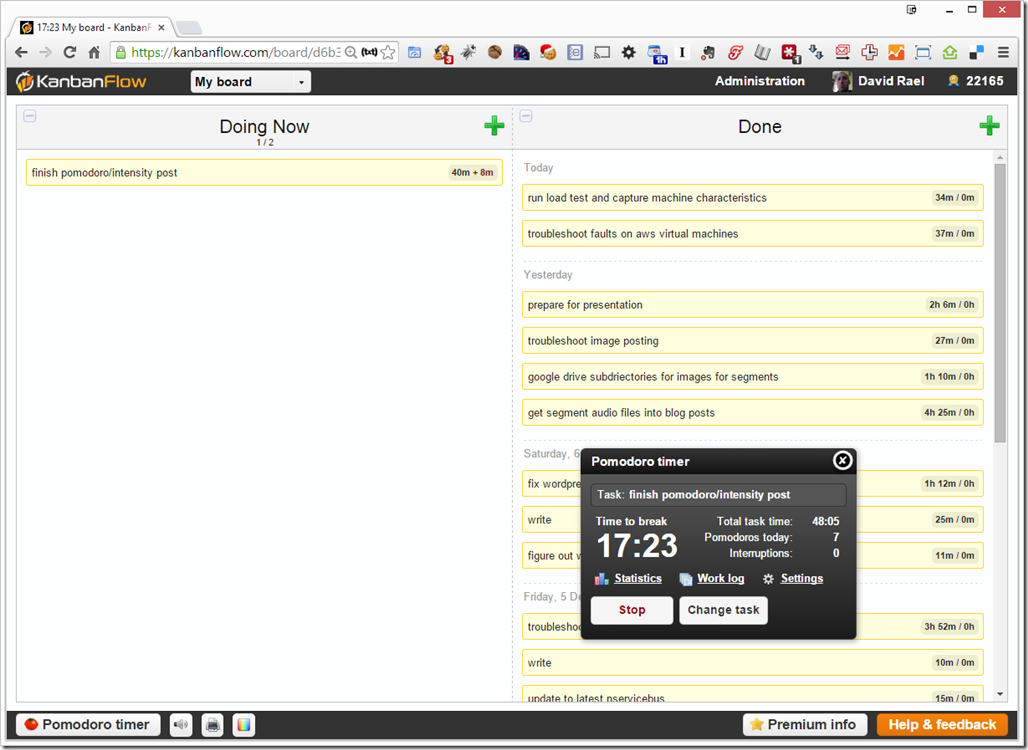

There are tools that associate Pomodoro timers with task tracking. The one I have been using, having discovered it in the comments on a post (I’m not finding the specific post at the moment) by John Sonmez, is KanbanFlow. I have seen that John has started using it as well. It is a Kanban board application, a lot like Trello, but it also has an integrated Pomodoro timer. I don’t really like planning my tasks on a Kanban board, especially for a week at a time like John does. That’s too much on there and it doesn’t serve me well to have so many things that I haven’t done staring me in the face. I prefer to use my email inbox and calendar for that and I will write a post about my processes and planning and task management in the near future. This keeps things out of my mind except for what needs my focus at the moment. I still like KanbanFlow, though because it is a web-based Pomodoro timer that I can use on any machine on which I am working and it keeps track of my Pomodoros and the time I spend on every task. In addition, columns can be configured such that they are partitioned into days.

Update:

I have written the post promised above about my email and task management techniques.

This means that the “Done” column can show tasks by which day they were done, for nice tracking records. It’s really useful. I have a single board on the site and it is set up with just two columns: one for Doing and one for Done. Typically I have only one task in my Doing column. I have it configured to allow for 2 so that I can context switch to something else if there is urgency on something and I need to do it. Going beyond two tasks will cause it to yell at me. That helps to keep me from cheating and putting too many things on the board and violating my process that is carefully crafted to enhance my productivity. I still need help with something that will prevent me from cheating on the Pomodoro technique – I struggle with stopping when the timer goes off, despite knowing it is in the best interests of my intensity and therefore my productivity. Despite my struggles, I am happy with the process and the tools I am using and highly recommend trying out Pomodoro.